The Night Atlanta Truly Became the City Too Busy to Hate

01-04-2016

When Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, the honor was a tremendous source of pride for the black community in King’s hometown of Atlanta. The majority of the city’s whites, however, were unimpressed.

“They thought it was just one more step in this process that was meant to deprive them of the fruits of white supremacy and Jim Crow law that they'd enjoyed for more than half a century,” recalls Frederick Allen, author of Atlanta Rising: The Invention of an International City and Secret Formula: How Brilliant Marketing and Relentless Salesmanship Made Coca‑Cola the Best-Known Product in the World. “If you had been waiting for the white community in Atlanta to accept Civil Rights, you would have waited as long as anywhere in the South.”

Allen notes that while the Civil Rights Movement was driven by the grassroots, bottom-up actions of Atlanta’s black community, the white response was completely top-down.

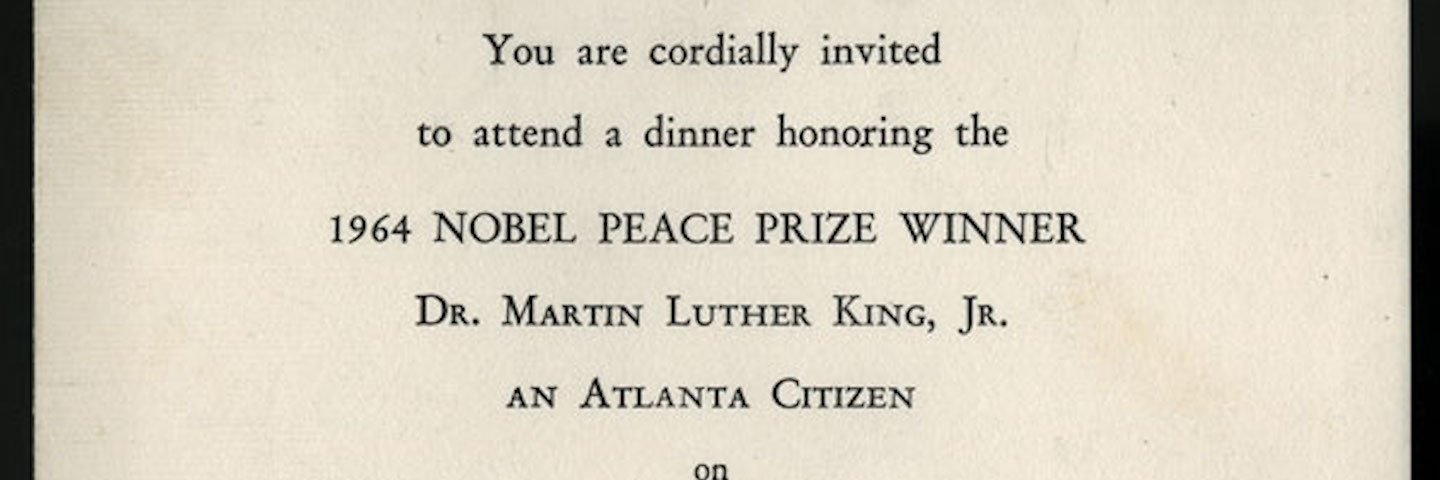

Case in point: After Dr. King accepted the Nobel Prize in Oslo, Norway, a small, diverse group of progressive Atlantans organized an interracial, interdemoninational dinner at the Dinkler Plaza Hotel to honor his achievement and unite the city’s largely segregated communities.

Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. offered to help drum up support from the city’s business community, but invitations to sponsor the landmark event were largely ignored by white leaders. One unnamed banker allegedly started making phone calls around town urging people not to go. Days later, a front-page story in The New York Times made Atlanta’s ugly story national news with the headline: “Tribute to Dr. King Disputed in Atlanta.”

That’s when Allen decided to call in a favor. Understanding the influence former Coca‑Cola president Robert Woodruff had on the city’s business community, he paid a visit to Woodruff’s Ichauway Plantation in southwest Georgia.

The mayor felt the lack of the support for the King dinner was an embarrassment to Atlanta, which had just launched a multi-million-dollar national advertising campaign touting it as “A City Too Busy to Hate.” Woodruff – who who had fallen off a horse and was recovering from injuries – agreed. He tapped Coca‑Cola President and CEO Paul Austin to convene the city’s business elite at the exclusive Piedmont Driving Club for a private meeting.

“They urged the leadership of the Atlanta business community, white folks, to buy tickets,” Frederick Allen said.

Austin was from LaGrange, Ga., but had lived and worked in South Africa for 14 years, where he saw first-hand how apartheid and racism wreaked havoc on the country’s economy. Determined to prevent a similar story from unfolding in Atlanta, he threatened to move The Coca‑Cola Company’s headquarters if his fellow executives didn’t step up.

“It’s embarrassing for Coca‑Cola to be located in a city that refuses to honor its Nobel Prize winner,” he is quoted as saying that night. “We are an international business. The Coca‑Cola Company does not need Atlanta. You all need to decide whether Atlanta needs the Coca‑Cola Company.”

By January 20, the dinner was sold out. “That broke the log jam and the tickets were gone,” said Frederick Allen. “The dinner went on and was a landmark of racial harmony."

More than 1,500 guests packed the Dinkler Plaza Hotel on Jan. 27, 1965, where Dr. King delivered an impassioned speech. The crowd – including many who had never dined with a member of the opposite race – even broke into an impromptu rendition of “We Shall Overcome.”

On Feb. 3, 1965, Ivan Allen sent a letter to Woodruff with a clipping from the Philadelphia Inquirer that spoke favorably of Atlanta and applauded the event that had “paid a deserved tribute to their good judgment and to their city.”

“This is a right sound editorial,” Allen wrote, “and is a reflection of the type of comment that I think we received over most of the country.”

Dr. King agreed. In a letter to The Coca‑Cola Company dated March 15, 1965, he wrote:

"Few events have warmed my heart as did this occasion. It was a testimonial not only to me but to the greatness of the City of Atlanta, the South, the nation and its ability to rise above the conflict of former generations and really experience that beloved community where all differences are reconciled and all hearts in harmony with the great principles of our Democracy and the tenants of our Judeo-Christian heritage."